Photo Credits to Ben Gebo Photography

University of St Andrews

srugheimer@st-andrews.ac.uk

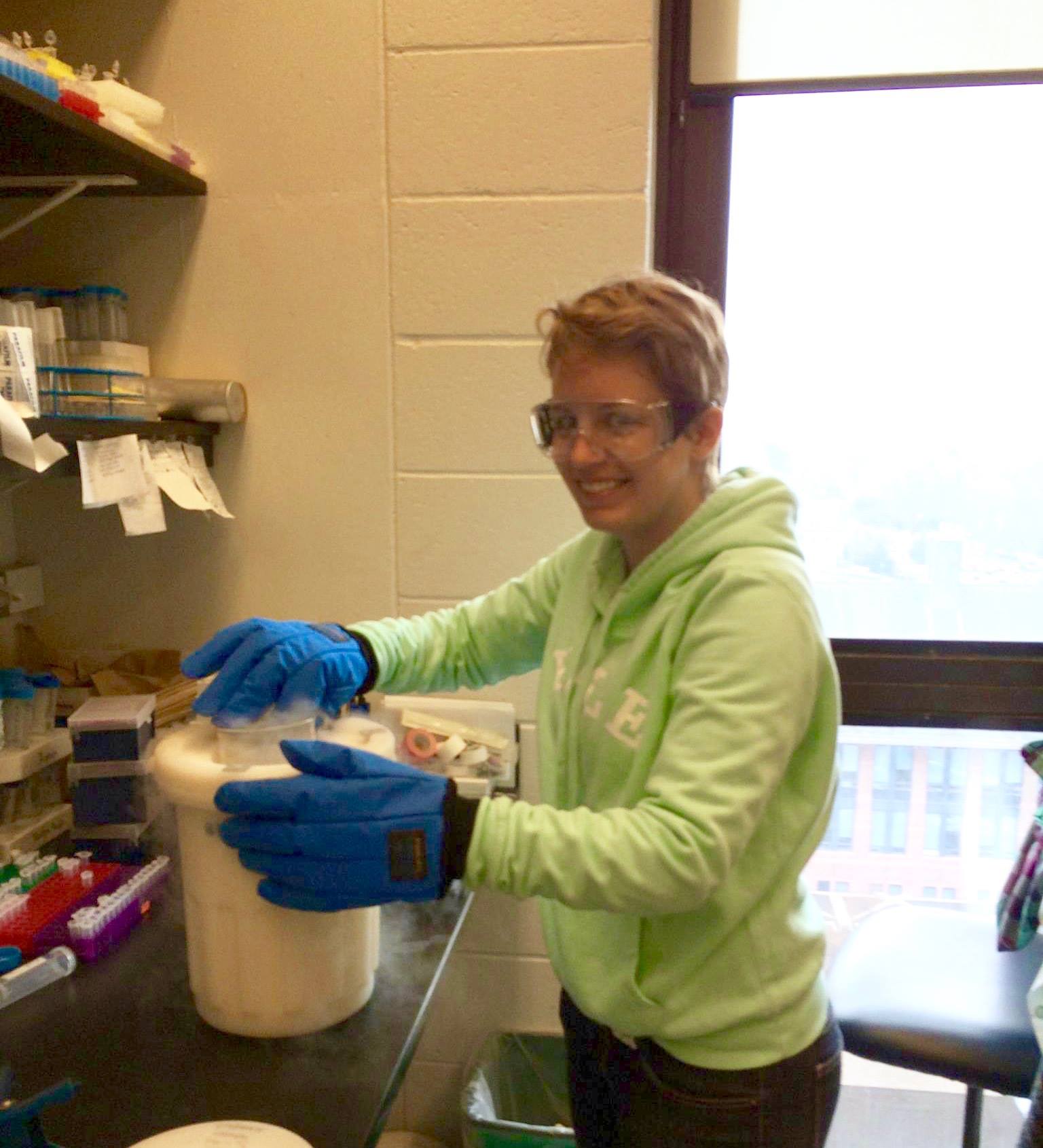

Dr. Sarah Rugheimer is an astronomer and astrobiologist, who is also a Simons Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of St. Andrews. She holds a B.Sc., in Physics from the University of Calgary as well as a M.A., in Astronomy and a Ph.D., in Astronomy & Astrophysics from Harvard University. To learn more about Dr. Rugheimer and her work, please visit her website! For more on navigating and surviving science culture, subscribe to Sarah's iTunes collaboration series called Self-Care.

What motivated you or inspired you to go into your field?

After finishing undergraduate with a degree in physics, I realized that though I enjoyed all of the research areas I had done as an undergraduate none of them gripped me so completely that I could imagine doing that for the next 40 years.

I then went to a conference in astronomy, a field I had previously not considered, and attended an astrobiology session on remotely detecting life on another planet.

My first thought was, “We might be able to do this in my lifetime!?” I was hooked.

I immediately started reading everything I could about the topic, and it has never lost my interest.

Knowing that my research will eventually contribute to answering this age-old question of “Are we alone in the Universe?” is what gets me excited to come into work every day. It was that moment, sitting in that conference, that inspired me to be an astrobiologist and pursue a PhD in astronomy. I think a lot of the opportunities for great growth in science lie at the intersection of traditional scientific disciplines.

Astrobiology is unique in that it combines all of science, from geology and astronomy to biology and chemistry. What I find most interesting about astrobiology is its potential to answer two big questions of humanity: how did life arise on Earth and is there life on other planets?

What were the first few steps you took to pursue your career?

In high school, I didn’t think I would end up doing science.

I liked writing and dancing as well as math and science, but most of my energies were in dance. I competed internationally in Irish dance and thought of opening my own dance school.

When I went to community college in my hometown in Montana, I realized that I really did enjoy physics and decided to major in it, continuing my undergraduate degree at the University of Calgary.

After graduating, I took a year off to travel and to think about what I wanted to do with my future, it was then that I found my passion within science: astrobiology. Because of my non-traditional path of going to a community college first, I didn’t think that I would be able to get into a place like Harvard and I almost didn’t apply.

I remember sitting at the computer for 5 minutes, staring at the submit button, asking myself why I should spend $90 on an application to a place that I had no chance of getting into. I hit submit and quickly closed the laptop.

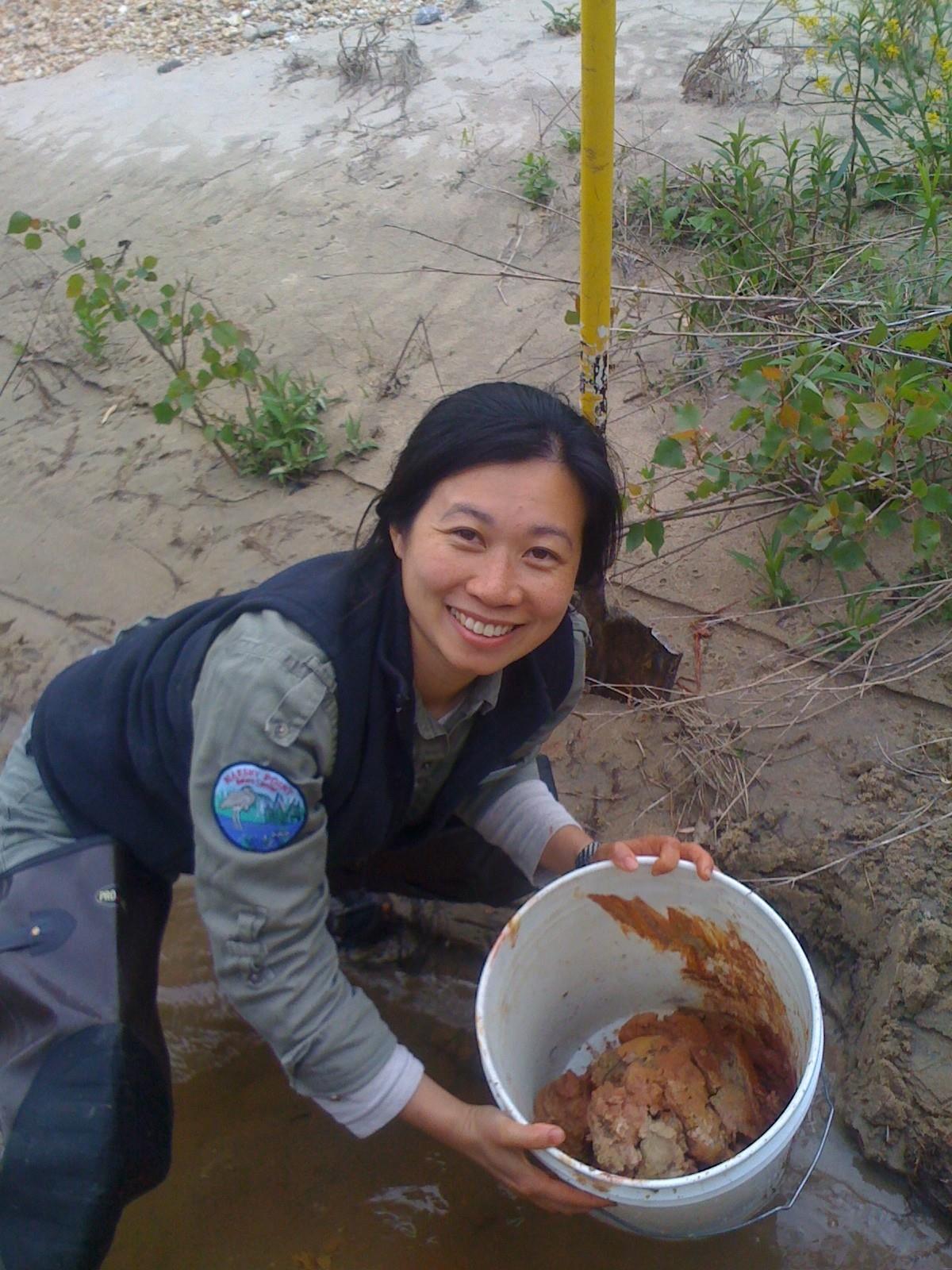

To my surprise, I was accepted to the Harvard and finished my PhD in astronomy & astrophysics there last year. Now I live in Scotland, with a Simons Origins of Life postdoctoral research fellowship at the University of St. Andrews working in a geoscience department.

What is the environment like in your workplace? What are some of your responsibilities?

Academia, especially non-lab based research like my own which largely depends on computer modeling, is very flexible. Instead of being tied to a 9 to 5 office job, I can work the hours and from locations that best suit my productivity and personal needs. The academic environment is always stimulating since it brings together curious people who are trying to discover new things about the world, our society, and our Universe. My main responsibilities now are to do research as well as to mentor students and advise the next generation of scientists. I am also very excited to teach a new interdisciplinary class next year in astrobiology at the University of St. Andrews.

What has been the most rewarding about your career?

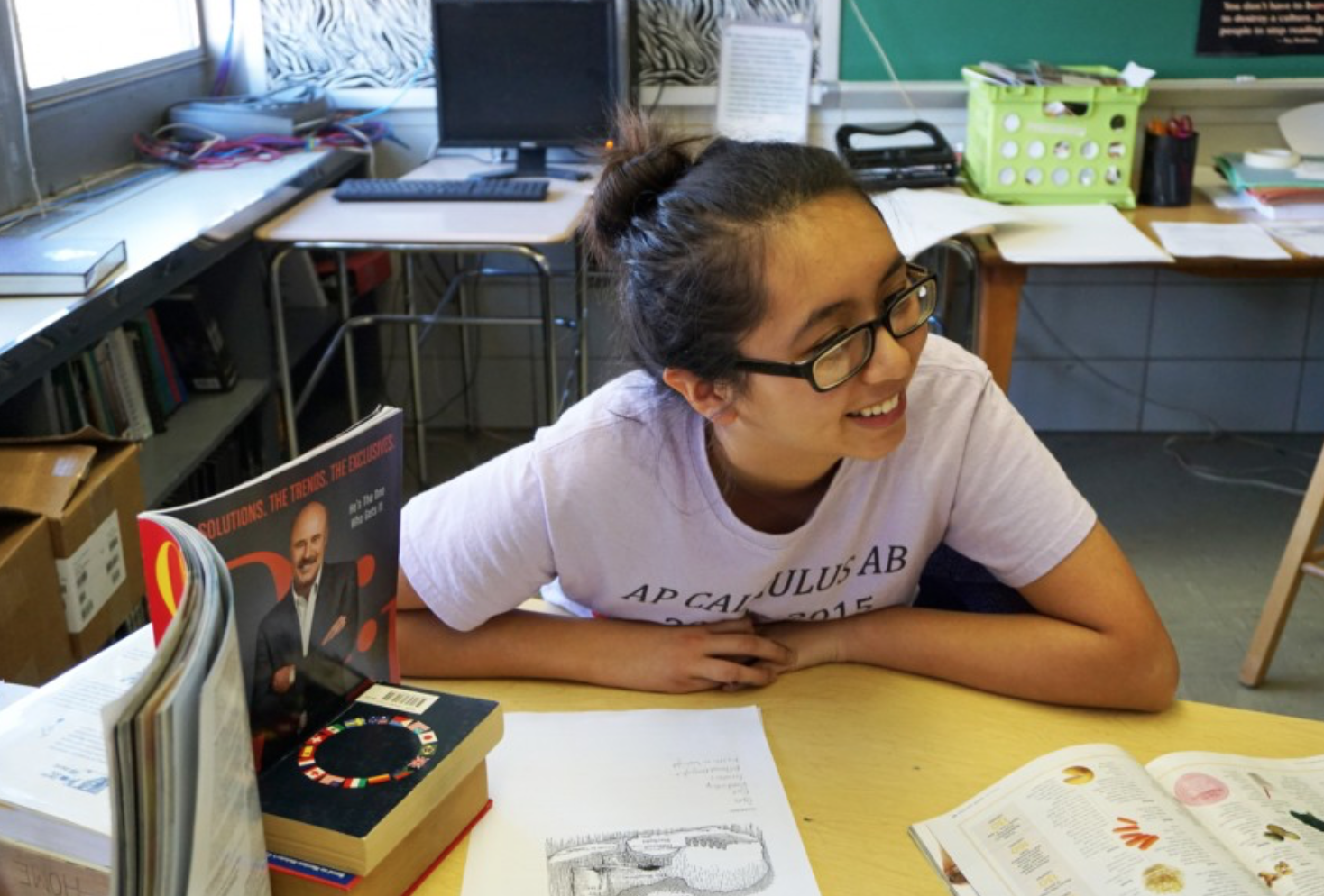

I love teaching and interacting with students. Getting someone passionate about science and astrobiology is the best reward of my job.

What have been your biggest challenges so far? How do you maintain positivity and motivation despite obstacles or barriers?

One of the biggest challenges I faced was in my first year of graduate school at Harvard. I felt so dumb compared to my peers. I was convinced that they knew everything and that it was only a matter of time before they would realize that it was a big mistake for them to have let me into the program. Every time I listened to a fellow classmate speak I assumed that they understood everything we were learning and were just naturally brilliant, whereas I was struggling to keep up. I’ve since realized that many people feel this way. All of my classmates likewise thought that they were dumb and I was the smart one, every one of us living in fear that we would be soon revealed to be not as smart as everyone else thinks we are. This phenomenon is called the impostor syndrome, and it’s the reason I thought about dropping out of school at least 6 times in my first year. But I didn’t drop out. On late night phone calls with my Dad, he urged me to just finish the first year and that it would get better. I reached out to my friends in the program and found out that they had the same insecurities and fears I did, though for a long time I was convinced that I was the true impostor and that my clearly brilliant friends were fake impostors. It took me many years to realize this pattern in my thoughts and through the support of friends, family and though seeking counseling I was able to recognize and combat the impostor phenomenon. Specifically, my internal impostor script tells me that I am not good enough to apply for this fellowship, that award or this grad school. Instead of listening to that script, I have realized that this phenomenon is real and that I should still apply to these opportunities without pre-selecting myself out of the application pool. Because of this, I ended up getting into a great grad school, was selected as one of 8 PhD students at Harvard to highlight their research, and now have a prestigious prize post-doctoral fellowship. All of these opportunities I might have missed if I would have listened to my impostor thoughts which tried to convince me that I wasn’t good enough for these opportunities. Instead I’ve learned to not let the impostor syndrome stop me from pursuing my scientific career goals and aspirations. Because of my experience, I am now passionate about helping others thrive with the impostor syndrome in academia. Last week I ran a workshop on the impostor syndrome during a summer school and I co-host a pod-cast with a friend, Dr. Sarah Ballard, called “Self-care with Drs. Sarah” where we discuss our real impostor thoughts and how to thrive in your work by first taking care of yourself.

What motto or core values do you live by?

I have two main mottos I live by. One is a quote by James Berry: “The Life of Every Man is a diary in which he means to write one story, and writes another. His humblest hour is when he compares the volume as is with what he vowed to make it.” Living life on autopilot sometimes prevents us from being who we want to be. I try to live each day mindful that our time on Earth is short and to actively do the things I am passionate about. The other was popularized by the vlogbrothers, Hank and John Green: “DFTBA or Don’t forget to be awesome.”

What kind of obstacles are in store for today’s young women? What are some words of advice you believe will help girls today overcome these obstacles?

The biggest obstacle facing young women in science today is the perception that women are now treated equally. I remember thinking this as an undergraduate, that this battle for equality had been fought and won decades before. But what I have now seen is that sexism (and racism) is alive and well but it is hidden enough that many people, both men and women, think it is no longer a serious issue. It has been shown in recent research that the exact same science resume, with just the name switched from John to Jennifer, will be deemed less hirable, less competent, less mentorable and given a 12% lower starting salary. Science published by women is cited less in the literature and women need to have on average more publications than men to be perceived equal. All of these biases are subconscious. And the key is that young women are just as likely to have these subconscious biases as old men because it is a cultural phenomenon, not a reflection on someone’s individual bias. The good news is that there is more awareness of this implicit bias phenomenon and I hope that we are beginning to finally close the last remaining gap for white women and men and women of color in the sciences.

Check out Sarah's speech at Harvard about extraterrial life!